Stagecoach robbery in the Old West was a risky endeavor. Authorities thwarted, caught or killed most road agents within a few attempts. (The same holds true for bank robbers, then and now.) Had such outlaws approached their “work” more cautiously, they might have avoided prison time (or worse) or at least postponed their day of reckoning. Charles E. “Black Bart” Boles, the most successful of Western highwaymen, was a true master of his profession, if unworthy of emulation. Had he written a handbook, it might have read like the following.

Planning

Study the stagecoach line schedule and, if possible, get advance intelligence on what a stage is carrying. While the presence of an armed “shotgun messenger” in the seat up beside the driver suggests a valuable cargo, it increases the likelihood you’ll have to exchange fire and might not survive the robbery. Black Bart sought to avoid messengers, preferring the prospect of reduced profits to the risk of armed resistance.

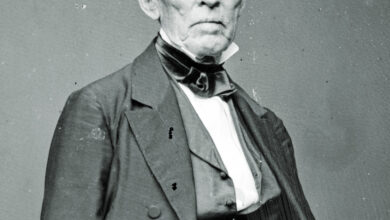

(Bettmann (Getty Images))

Scope out the terrain beforehand and pick the holdup site carefully. It should be a remote location, preferably at the brow of a hill, a bend in the road or another spot that will force the driver to slow down. Make sure there is sufficient roadside concealment and stash any horses you might need for a getaway well away from the holdup, as the horses pulling the stage might react to them and alert the driver.

Partners

You are well advised to have as few partners as possible. The fewer partners, the fewer ways you’ll have to split the proceeds. More important, you’ll run less risk of someone getting caught and “peaching” on you. Assume your partner—no matter how close a friend or relative—willspill the beans if caught, as the prospect of a reduced sentence is a powerful inducement. Black Bart always worked alone.

Equipment

Most road agents’ firearm of choice is a shotgun, which is simple to operate and sufficiently intimidating. Black Bart used a double-barrel he later claimed was never loaded. On the two occasions he did meet with armed resistance, he fled—a good example to follow, however humiliating. You’ll live to rob another day.

Express companies like Wells, Fargo & Co. use heavy wooden boxes or metal safes, the latter often bolted to the floor of the coach. Be sure to bring a pick, hammer and cold chisel or similar set of tools capable of opening a box or safe.

On Dec. 4, 1875, highwayman Dick Fellows waylaid the Los Angeles-to-Bakersfield stage and secured the express box without incident. But in an egregious instance of bad planning, he lacked tools to open it. When Fellows tried to load the strongbox on his horse, the unfamiliar burden spooked the animal, causing it to bolt. Then, while dragging the box to a hiding place, Fellows toppled off a railroad embankment and broke his left leg and foot. Concealing the box as best he could, he limped to a nearby farm and stole another horse. But a local posse was soon on Fellows’ track, as the stolen mount wore a readily identifiable mule shoe on one hoof. The luckless road agent was quickly

caught and arrested, all for the lack of a pick.

Technique

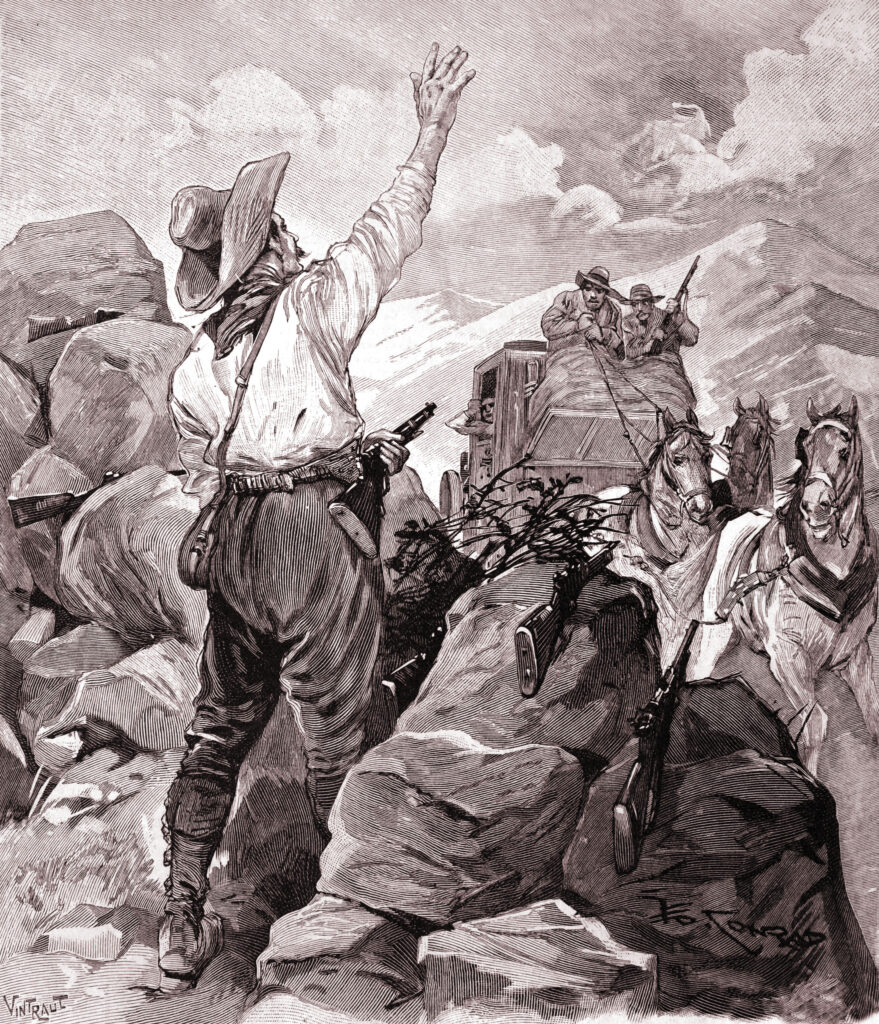

One should carry out the actual robbery afoot. As the stagecoach approaches, step from hiding into the path of one of the lead horses. That both prevents the team from moving and discourages gunfire, as it places you close to a valuable animal.

Next, level your weapon and make your demand. Speak as little as possible. Disguise yourself beforehand with a hat and a mask and conceal any tattoos or distinctive scars. Again, keep your horses well out of sight, as they, too, might link you to the scene.

(Chris Hellier/Corbis (Getty Images))

Passengers

It is best to avoid robbing passengers, as it will take precious time for them to hand over valuables, and one might get bold and offer resistance. If you insist, treat them as gently and courteously as possible. Nothing motivates a sheriff’s posse—or, worse, a vigilance committee—like reports of passenger abuse. When eight men robbed a stage bound from Virginia City, Montana Territory, in Portneuf Canyon on July 13, 1865, killing four passengers and wounding the messenger, vigilantes pursued five of the bandits into Colorado Territory and summarily hanged them—legality and jurisdiction be damned.

Black Bart was overtly polite to passengers, especially women, and never robbed them.

Getaway

Be certain your getaway horses are healthy, well-fed animals, capable of outrunning or outlasting those of a posse. Borrow a page from Jesse James. While the James-Younger gang seldom robbed stages, preferring banks and trains, Jesse carefully chose his horses and was deft at escaping mounted posses.

For his part, Black Bart always escaped afoot. Exceptionally fit for a man in his 40s and 50s, he could travel long distances through rough terrain that might deter a horse.

It is best to depart the area entirely to avoid local sheriffs, marshals and posses—all of whom are limited in their geographical jurisdiction. Of course, that won’t help if U.S. marshals, Pinkerton men or Wells, Fargo agents are after you, as they aren’t restricted by county or state boundaries. Likewise, vigilantes are the wild card you never want to draw.

Disposal of the Proceeds

Spend the proceeds quietly. In the Portneuf robbery described above, stage driver Frank Williams was suspected of collusion with the bandits and later observed living it up in Salt Lake City. Vigilantes finally caught up with him in Colorado Territory and, after hearing his impassioned confession (which implicated his partners), hanged him from a cottonwood tree.

Last Word

Black Bart’s track record notwithstanding, stagecoach robbery is a poor career choice. Try, try again, and you’ll likely get caught. Even if you scrupulously follow the above recommendations, odds are you’ll ultimately wind up behind bars. Even Black Bart was caught in the end. Also note, the last known stagecoach robbery out West, at Nevada’s Jarbidge Canyon, took place on Dec. 5, 1916. All three suspects were arrested and imprisoned. The $4,000 in loot was never recovered. Now, treasure hunting—there’s a profession to consider.