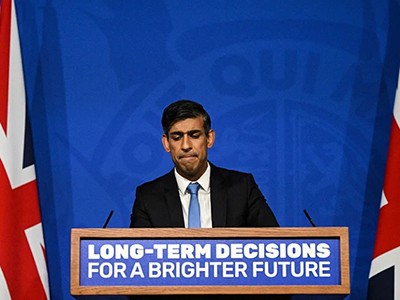

The UK heatwave in early September was the nation’s longest run of September days hotter than 30 °C on record — an illustration of climate change progressing and a herald of impacts to come. Yet, on 20 September, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the abrupt rollback of key climate policies in the country’s strategy to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

Sunak’s changes undermine UK efforts to build a climate-resilient future and have provoked an outcry from industry. The delays come at a time when independent opinion polls show that 49% of UK citizens want the government to do more to reach net-zero emissions, whereas only 18% would rather it did less. Moreover, progress towards meeting the country’s domestic climate targets is faltering.

The opposite of visionary, this decision looks set to disappoint citizens, businesses and the world. With a legally binding net-zero target for 2050, it means that either unpleasant, costly interventions will be required in a few years’ time to make up for today’s policy shortfall, or the United Kingdom will fail to meet its climate targets.

Shock delay to net-zero pledges turns UK from climate leader to laggard

The rollback notably covers policies that affect cars, heating and energy efficiency. Sunak presented it as a way to avoid interfering in “people’s way of life” and to help those struggling to make ends meet. But evidence suggests that in some cases these decisions are likely to have the opposite effect, costing people rather than benefiting them.

For example, Sunak delayed a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2030 to 2035, citing the current price tag of electric vehicles. This explanation is poorly founded, because the ban would not apply to the second-hand vehicle market, providing options for those who cannot afford a new electric car. Citing consumer costs as the impetus is strongly at odds with evidence from the UK Climate Change Committee — an independent advisory body — showing that keeping the 2030 phase-out date would save citizens more than £6 billion (US$7.3 billion) between now and 2050 (see go.nature.com/3eudna6).

Furthermore, landlords are no longer required to ensure that rental properties meet a minimum energy-efficiency standard. Sunak presented this as a way to shield renters from rent increases, but an independent analysis shows that efficient homes can save households hundreds of pounds a year. Instead of slashing energy-efficiency requirements, the government could simply pass measures that directly protect renters from price increases.

Several of Sunak’s statements pretend to abolish plans that were never policies in the first place — from taxing meat or frequent flying to requiring carpooling or increasing the number of types of recycling bin. One thread that binds all of these straw-man measures together is that they require behavioural changes. But evidence from UK citizen assemblies suggests that well-informed people strongly want to make behavioural changes and want the government to support them in achieving such changes.

Net-zero pledges are growing — how serious are they?

Besides being costly to individuals over the long term, the policies’ uncertainty and unpredictability also worries businesses. Hundreds of companies, including Ford, Eon, IKEA and Nestle, have said in response to Sunak’s decisions that unstable long-term policies undermine business confidence, the mobilization of finance and the credibility of the United Kingdom as a place for ‘green’ investment. The country’s failure to interest bidders in building further offshore wind-energy capacity at a September auction adds to this image. Ultimately, absent or volatile policy guidance is a barrier to flourishing technological innovation.

Sunak speaks of the country’s previous decarbonization successes as though they were enough — but past reductions were achieved in relatively straightforward sectors, such as energy, in which coal has been almost completely replaced, mainly by renewable sources, although fossil-gas use has continued. Domestic reductions in emissions have also been partially offset by an increase in the emissions of imported goods. The difficult task of decarbonizing transport, industry and building sectors is still ahead, and will require both a long-term vision and immediate investments to drive lasting structural changes. Although Sunak has expressed confidence that medium-term targets will still be met, the UK Climate Change Committee found the opposite for the more challenging sectors in its annual assessment of gaps in the government’s decarbonization policies.

On the world stage, these policy changes show that the United Kingdom is turning its back on a global leadership position while the United States and the European Union are using the transition to climate resilience as an opportunity to lead. The United Kingdom could confidently be a global climate leader, having spearheaded the first comprehensive domestic climate legislation in 2008, set a legally binding net-zero target in 2019 and hosted the COP26 climate summit in 2021. Instead, it has weakened its diplomatic weight and might need to brace for a cool reception when explaining its choices to low- and middle-income countries.

The United Kingdom has a broad base of public and political support for climate action, so the prime minister cannot lay this decision at the feet of the public. What people want and businesses need is clear: effective climate policies to reach net-zero emissions, creating a prosperous economy and a liveable world for all.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Source link