Today we are fortunate to have as a guest contributor Joseph Joyce, Professor of Economics and M. Margaret Ball Professor of International Relations at Wellesley College.

Current account data are scrutinized carefully for signs of potential or actual volatility. Deficits that seem justifiable under current conditions may have to contract if there is a sudden outflow of the foreign capital that sustains them, as occurred in Mexico in 2014-15. The IMF’s 2023 External Sector Report Policy, for example, list countries with weaker external positions than desirable. The 2023 report includes Argentina, Belgium, Canada, France, Italy, South Africa, Turkey and the U.S. in that category.

Prescriptions on how to deal with a current account deficit point out the need to adjust the savings-investment imbalance, using expenditure switching and/or expenditure reduction measures to adjust the trade balance. Recent papers by Kolerus, “What Shapes Current Account Adjustment During Recessions?”, 2021, and Bergin, Kim and Pyun, “Fear of Appreciation and Current Account Adjustment,” 2023, offer analyses of this issue. But a closer look at current account deficits reveals that not all deficits have the same components. The current account includes the trade balance, the net primary account which is dominated by investment income, and the secondary income balance, which includes personal transfers. The respective positions of the latter two accounts can complicate policy prescriptions.

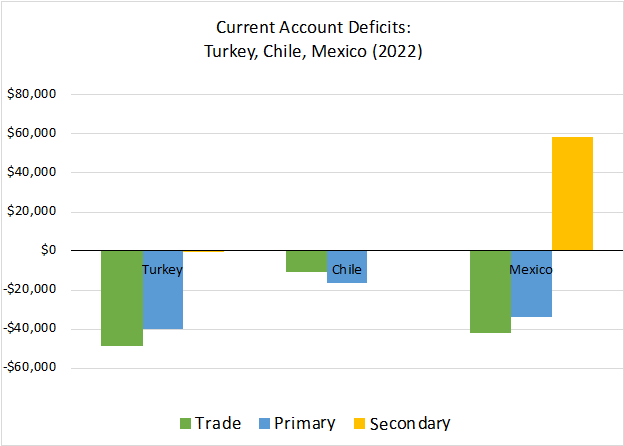

To illustrate this point, consider the current account deficits of three emerging market economies: Turkey, Chile and Mexico, which have current account deficits. Turkey’s deficit in 2022 was $48,751 million. The main source of this deficit was the trade balance, which registered a deficit of $39,812 million. A relatively small primary income balance deficit of $8,565 million also contributed to the current account deficit, while the secondary income balance was negligible. Articles about Turkey’s current account rightly point to the trade deficit as a major factor.

Chile in 2022 registered a current account deficit of $27,102 million. But the biggest component was not its trade deficit of $11,016 million, but the primary account deficit of $16,520 million. This figure, in turn, reflected a direct investment income deficit of $13,267, the product of FDI inflows. A secondary income surplus of $434 million was too small to have a major impact. Any changes based on an exchange rate devaluation would need to bear in mind if and how the primary balance would change.

The final case to consider is that of Mexico, with a 2022 current account deficit of $18,046. Its trade deficit of $42,292 million was much larger, as was the primary income deficit of $33,831. How did Mexico manage to have a much lower current account deficit? The answer, of course, is the positive secondary income balance of $58,077 million. The latter shows the contributions of personal transfers by Mexican workers abroad. Its situation is not unique; Egypt has a similar configuration in its current account.

Can the primary or secondary account be adjusted to reduce a current account deficit? Begin with the configuration of the three countries above, with trade and primary account deficits and some remittance inflows. Would the reaction of the primary account to a depreciation bolster or dampen the trade account response? The immediate impact on an income earned on assets in a foreign currency should be to reinforce a rise in the trade account, while liabilities denominated in a foreign currency would offset it. A continuing deficit that needed to be financed would increase the country’s liabilities, thus worsening the income deficit.

Empirical analysis by Alberola, Estrada and Viani, “Global Imbalances from a Stock Perspective” (2020), show that in the case of the debtor countries the trade balance contributes to rebalancing the current account, which offsets the deterioration due to the income channel. In the case of a debtor economy, the trade balance channel offsets the worsening impact of the income balance. Colacelli, Gautam and Rebillad in “Japan’s Foreign Assets and Liabilities: Implications for the External Accounts” (2021) examine the case of Japan, and report that the income balance response to real exchange rate movements is smaller than the trade balance response. They also report that the main external rebalance response occurs via the trade balance, but the income response dampens it in debtor nations. Behar and Hassan, “The Current Account Income Balance: External Adjustment Channel or Vulnerability Amplifier? (2022), define the income balance to include both the primary and secondary accounts, and find that the income balance does not have an important role in stabilizing the current account. The results of all three papers imply that an assessment of the measures needed to a deal with a current account crisis should include the possible deterioration of the income balance.

Personal remittances are a major factor in the net secondary income, although there are times when government transfers predominate. For many emerging markets, these inflows partially offset the deficits in the trade balance and international investment income. Could they be used to dampen the impact of a crisis? Much would depend on the resulting savings-investment balance responsible for the deficit. Are the funds from abroad used for savings or consumption? If the latter, are the goods imports or domestic? In addition, a number of studies have shown that inflows can appreciate the exchange rate, a phenomenon known as the Dutch disease (Acosta, Lartey and Mandelman, “Remittances and the Dutch Disease” (2009), Lartey, Mandelman and Acosta, “Remittances, Exchange Rate Regimes and the Dutch Disease” (2012).

There are relatively few studies that have investigated the linkages of remittances and the current account. Bugamelli and Paterno, ”Do Workers’ Remittances Reduce the Probability of Current Account Reversals?” (2009), presented evidence that larger remittances in terms of GDP reduce the probability of a sharp current account adjustment due to a fall in international reserves. Hassan and Holmes, “Do Remittances Facilitate a Sustainable Current Account?” (2016) find that larger remittances lead to a faster adjustment of the current account in response to shocks. Lartey, “The Effect of Remittances on the Current Account in Developing and Emerging economies (2019), on the other hand, finds evidence of a positive contemporary effect but a lagged negative impact.

Other changes could affect both income balances. A contraction in national income, for example, could lower the profits of multinationals and the income deficit, while migrants who live abroad may raise the amount of funds that they send to their home countries. A worldwide downturn, on the other hand, lowers the returns on all earnings, while the migrants may lose some or all of their income in their host countries.

The impact of international factor income, therefore, deserves more attention, particularly as the primary and secondary income balances become more significant components of the current account. The trade balance will continue to be the main focus of attention, but investment income and remittances can worsen or moderate a current account imbalance. Policies to rectify a crisis by reversing a trade balance deficit will need to take these other imbalances into account.

This post written by Joseph Joyce.

Source link