Today we present a guest post written by Lindsay Jacobs, Assistant Professor at the Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Since 2021, Social Security retirement benefits have exceeded the revenue generated by payroll taxes. The shortfall has been covered by drawing from the Social Security Trust Fund, which is projected to be depleted by 2034. At that time, we’ll face a “fiscal cliff” for this self-funded program where payroll taxes will only cover about 80% of the benefits, resulting in an automatic 20% reduction in payments to retirees.

Nearly all workers and retirees will be affected, so there is broad interest in reforms that would avert this sudden drop in benefits. However, this outcome is in the future, so the dilemma is that while any reform is better than inaction, each comes with immediate costs. Considering this, the limited legislative momentum seems unsurprising.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) has published updated projections showing how various reforms could impact the program’s solvency. You can find a summary here, and more detailed analyses here. There are dozens of possibilities, most being variations on either benefit reduction or payroll tax increases. Two frequently discussed reforms are raising the retirement age and raising or eliminating the payroll tax cap. Other, less prominent proposals involve adjusting how benefits and earnings histories are calculated to account for inflation and real wage growth.

In my view, successful reform will likely involve a mix of approaches in order to maintain the program’s objective of poverty reduction in old age while preserving the broad public support that Social Security has enjoyed.

Here’s how I am thinking about the tradeoffs of four particular reform possibilities—not as a policymaker but simply as an interested researcher. It’s more of a novel than I had expected, but it turns out there’s a lot to consider!

Reform 1: Raising the Full Retirement Age

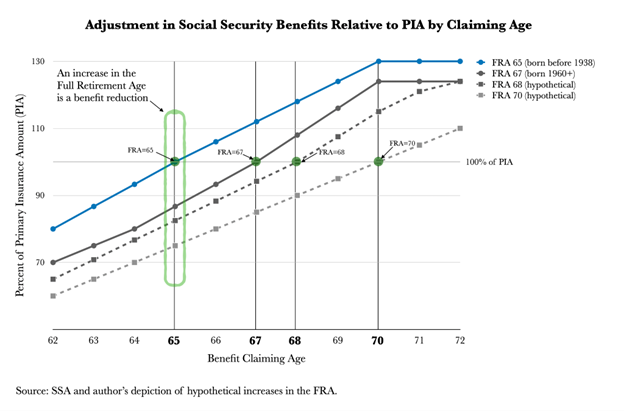

The Full Retirement Age (FRA)—the age at which beneficiaries can receive their full Primary Insurance Amount (PIA)—was gradually raised from 65 to 67 following significant reforms in 1983. Surprisingly, these were the last major changes to the program. Since then, proposals have surfaced to gradually raise the FRA further to 68, 69, or even 70, with the rationale being that increases in life expectancy justify a later retirement age.

This change would be quite effective in improving Social Security’s solvency. For example, raising the FRA gradually to age 69 would reduce the program’s shortfall by about 38% over the next 75 years. (Scenario C1.4 in SSA’s projections.)

I would argue that there are additional distributional effects of increasing the FRA across occupations, given the differences in claiming age behavior and there being an even greater penalty on groups of people who tend to claim early. In particular, people in blue-collar jobs, regardless of their income level, tend to retire earlier and would be more negatively impacted by an FRA increase. I discussed this in a past EconBrowser article and this paper further explores the issue.

Raising the FRA is not an especially popular reform. While it is effectively a benefit cut, as shown below, it doesn’t require delaying benefits altogether; the option to claim benefits before the FRA—at the Early Eligibility Age (EEA) of 62—would still remain, albeit at reduced levels. If this point were emphasized, I think the idea might face less resistance.

An increase in the earliest eligibility age would be a far worse outcome for those who are already claiming as soon as possible—notably many blue-collar workers. Raising the EEA would likely also have the effect of directing more people toward applying for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI).

I wouldn’t be in favor of increasing the FRA dramatically or the EEA at all because they make benefits far less progressive in practice, and less in line with the purpose of the program. A moderate increase in the FRA to 68 seems agreeable, at least when considering the alternative of across-the-board benefit cuts that would come with insolvency.

Reform 2: Increasing the Taxable Wage Base

The wage base for Social Security payroll taxes includes all income up to the current annual maximum of $168,600, and is taxed at 12.4%, split between employers and employees. Any income above this cap is not subject to the tax, and no additional benefits are earned. Today, about 6% of workers earn more than this threshold. While benefits are highly progressive, payroll taxes alone are somewhat regressive.

One of the more ambitious proposals to expand the wage base is to lift the cap entirely, taxing all income while maintaining the current benefit formula. This could eliminate about 60% of the projected funding shortfall over the next 75 years (as shown in Scenario E2.17 in SSA’s projections). A variation of this proposal was included in the Social Security 2100 Act (H.R. 4583), which would subject income above $400,000 to the payroll tax, while excluding income between $168,600 and $400,000. This creates a “donut hole” that would shrink over time as the taxable maximum increases with wage growth.

Eliminating the payroll tax cap altogether would certainly strengthen the Social Security program financially but would come with many downsides. A real concern would be the unknown but likely very large labor market effects; high earners and their employers would surely seek ways to restructure compensation to avoid the tax. Even if one were sympathetic to higher tax rates for higher earners, is Social Security solvency the highest priority use of those revenues?

Another issue is the possible decline in support for the program. The program is currently very popular, in part because benefits are broadly seen as fair—highly progressive, but still linked to taxes paid. Removing the cap would weaken the connection between contributions and benefits, which may erode support among higher earners. Even if additional benefit credits were offered to those paying higher taxes, this wouldn’t be very appealing to wealthier individuals who have other preferred savings options.

One way to mitigate some of these concerns might be to impose a lower tax rate on income above the current cap, which could soften the impact on high earners and make the reform more palatable.

There’s a convincing argument for expanding the taxable wage base, but such a reform would likely need to be tempered. Currently, 83% of total labor earnings are subject to Social Security taxes, down from over 90% in the years following the 1983 reforms. Although the taxable maximum adjusts for wage inflation, income inequality has grown, meaning a greater share of earnings now exceeds the cap. A reform that could address this issue would be to raise the maximum income taxed to cover 90% of taxes, instead of indexing to growth in average wages. This would put the cap at about $300,000 currently. A good argument against doing so is that what has pulled up the average earnings is not so much the top 10% of earnings but rather the share at the very top.

Reform 3: Reducing the Real Growth of Benefits

One subtle but highly effective reform would involve adjusting Social Security benefits using changes in overall price levels instead of wage levels to calculate past earnings and corresponding benefits. While average wages have outpaced inflation—reflecting real productivity growth and resulting in benefits that grow faster than the cost of living—this reform would slow that growth. According to the SSA’s projections (Reform B1.1 in their projections), this change alone could eliminate 85% of the Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years.

To see why this would have such a large effect, it helps to think about how benefits are calculated. Benefits are based on a person’s birth year, the age at which they claim, and their top 35 years of earnings. These past earnings are adjusted for wage inflation to determine a person’s Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME), which is then used to calculate their Primary Insurance Amount (PIA)—the monthly benefit they would receive at Full Retirement Age (FRA). Adjustments are made if someone claims earlier or later than their FRA. Because nominal wage growth is nearly always higher than price inflation due to rising real productivity, the cumulative effects of transitioning to price inflation-based adjustments would significantly slow the growth of benefits over time. While we would all prefer more salient reforms, the complexity of this reform might—however unfortunate—actually make it more politically feasible.

The conceptual argument for this reform is that the current wage-level adjustments to benefits are excessive, increasing retirees’ benefits well beyond purchasing power.

An argument against it is that as productivity rises, retirees should share in the gains from rising living standards through benefits linked to wage growth. After all, if people could have instead invested what they paid in Social Security taxes over the years, their returns would be higher than inflation.

I’m partial to both lines of reasoning. However, I think the primary advantage of this reform is that it’s simply very effective at improving solvency while also disbursing costs over time.

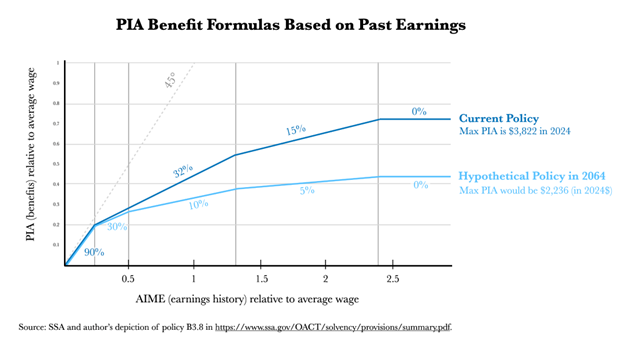

Reform 4: Modifying the PIA Formula to Reduce Benefits for Higher Earners

Another potential reform is to modify the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) formula in a way that reduces benefits for all but the lowest earners. This would protect lower-income retirees from across-the-board benefit reductions, whether those result from raising the Full Retirement Age (FRA), changing how past earnings are calculated, or any number of other reforms. It would also significantly improve Social Security’s solvency.

To see what this looks like, I graphed the current PIA “bend points” and factors, alongside the reform projection in B3.8, which would gradually adjust the PIA formula over four decades and eliminate 29% of the program’s shortfall over the next 75 years.

This would make the program even more progressive, which would understandably reduce support as it weakens the link between the taxes people pay and what they can expect to receive.

Despite this, it seems reasonable on the grounds that it would go a long way in improving solvency, while aligning more closely with the program’s original purpose of reducing poverty at older ages.

Moreover, implementing the changes over a longer time horizon would give those who are capable of saving to adjust their plans well in advance of retirement—very desirable when considering the alternative of sudden and uncertain drops in benefits.

Choosing the Least Worst Options

Ultimately, I think the goals of Social Security reforms should include:

- Achieving solvency to meet current obligations and provide certainty for future retirees.

- Ensuring income replacement and protection against poverty in old age, in alignment with the program’s original goals.

- Preserving the broad support Social Security has traditionally enjoyed.

Given these objectives—and considering the reality that the alternative is no reform, which will lead to sudden benefit cuts—I would advocate for a combination of the following: reducing benefits for high earners over time (Reform 4), adjusting how past earnings are indexed (Reform 3), and moderately increasing the taxable wage base (Reform 2). Taken together, a more tempered version of each could be implemented to achieve solvency.

Of these, the most effective in achieving these goals would likely be reducing benefits for higher earners (Reform 4), implemented gradually. Some form of this would align Social Security more closely with its original intention as a “safety net” aimed at preventing poverty in old age, rather than a full retirement savings program. Because people with higher earnings histories tend to save far more privately, a reduction in benefits might be preferred to payroll tax increases that might otherwise arise.

A moderate increase in the taxable wage base, covering closer to 90% of total earnings, contributes very effectively to the program’s immediate solvency. Since changes to the benefit formula would take time to phase in, at least some near-term tax increases are necessary. Adjusting how past earnings are indexed—moving toward a measure between wage and price inflation—would also help achieve solvency while being more neutral than other forms of benefit reductions.

With these options available, I wouldn’t favor raising the Full Retirement Age (Reform 1), as it disproportionately affects those who for various reasons claim earlier, particularly those in physically demanding jobs, and would likely increase reliance on Disability Insurance (SSDI), which I’ve looked at here.

The last significant reforms in 1977 and 1983 occurred within a year of insolvency—so is that what we should expect? Perhaps, but the sooner reforms come, the better. For legislators, however, advancing unpleasant but necessary reforms are a mostly thankless job with many downsides. This could change if a sizable share of voters show concern. But this would require accepting the reality of no reform: Our current policy is an immediate reduction of 20% in benefits for all in only 10 years, a reduction that will only grow over time. Without this unfortunate alternative in mind, of course no reform looks appealing!

So, what do you think?

This post written by Lindsay Jacobs.

Source link