A hallmark of most breast cancers1 is the expression of a hormone receptor called oestrogen receptor-α (ERα). People with this type of cancer typically receive endocrine therapy, involving oestrogen-blocking drugs such as tamoxifen, but the development of resistance to this treatment is a common clinical challenge2. One way to enhance the effectiveness of endocrine therapy and delay the emergence of resistance is through periodic fasting, when, under clinical supervision, people restrict their eating and consume few or no calories for time spans of hours to days on a regular cycle. However, the mechanisms underlying this effect have been hard to determine3. Writing in Nature, Padrão et al.4 now provide some answers regarding the consequences of such fasting.

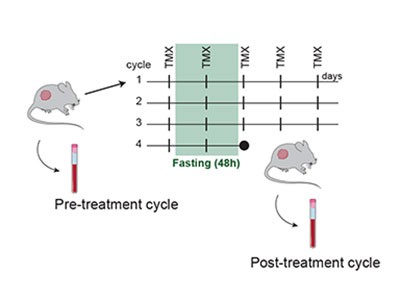

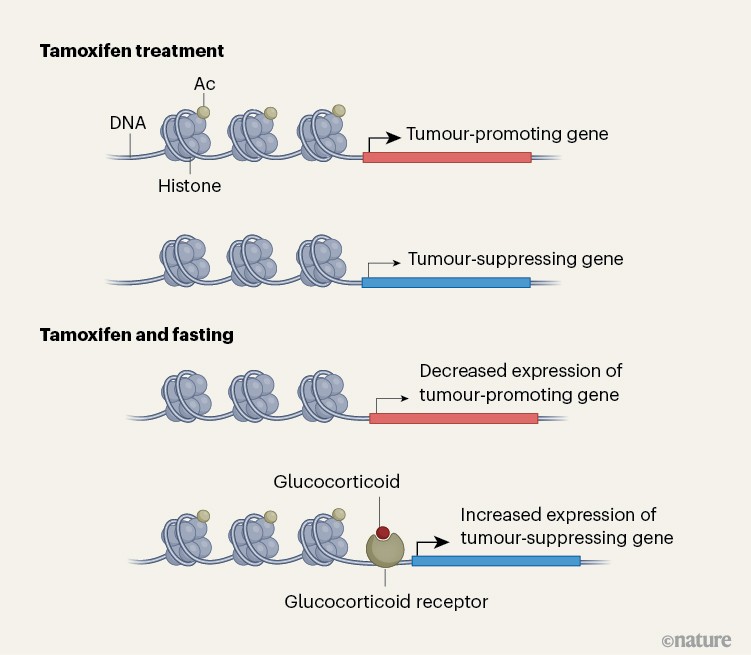

The authors present rigorous studies using several animal models of this type of breast cancer, together with methods to track various molecules in cells (multi-omic approaches). Padrão and colleagues’ findings demonstrate that fasting induces broad reprogramming of ‘epigenetic’ changes — alterations in DNA-binding proteins that modulate gene expression (Fig. 1). These switch on signalling pathways associated with receptors that are activated by the binding of hormones called glucocorticoids; the pathways suppress cell division and prevent the development of resistance.

Figure 1 | Changes in gene expression associated with fasting during treatment for breast cancer. Padrão et al.4 used mouse models to explore why fasting can be beneficial when breast tumours that express oestrogen receptor-α are treated with endocrine therapy (using drugs such as tamoxifen). The authors find that fasting is associated with modifications to the histone proteins that bind to DNA, including the addition of acetyl groups (Ac) that affect gene expression. These changes affect the expression of genes that can promote or suppress tumour growth. The authors also report that fasting during breast cancer treatment drives an increase in expression of the hormone glucocorticoid and that signalling through its receptor helps to drive expression of genes that suppress tumour growth. (Adapted from Fig. 4h of ref. 4.)

Signalling mediated by activated glucocorticoid receptors is a particularly potent mechanism of cancer suppression in ERα-positive breast cancers of a subtype known as luminal A. In other subtypes of breast cancer, the effect of activated glucocorticoid receptors might be non-existent or even enhance tumours. This subtype specificity might explain why previous trials of glucocorticoid treatment for breast cancer — conducted before breast tumours were subtyped using sex-hormone receptors — showed only modest benefits5,6, possibly because of the inclusion of ‘triple-negative’ cases of breast cancer. These are tumours that lack receptors for oestrogen, the hormone progesterone and the protein HER2; in this context, activation of the glucocorticoid receptor promotes tumour growth7.

Read the paper: Fasting boosts breast cancer therapy efficacy via glucocorticoid activation

Padrão and colleagues establish that molecules that activate glucocorticoid receptors, such as the steroid dexamethasone, mimic the antitumour effects of fasting and enhance the effectiveness of endocrine therapy without the need for dietary restriction, which can be challenging for most people to maintain. Together, these findings position the activation of glucocorticoid receptors as a promising strategy for boosting the effectiveness of treatment for ERα-associated breast cancer.

The findings have several implications that could advance approaches to treat or prevent this type of breast cancer. First, in a broad sense, the work underscores how the body’s metabolic status (in this case, during fasting or fasting-mimicking diets) can reprogram the epigenetics and receptor-mediated signalling of tumour cells, suggesting that modulation of metabolism should be more broadly considered as a component of cancer therapy. The observation that activation of glucocorticoid receptors is beneficial in ERα forms of breast cancer, but not in triple-negative breast cancer, highlights the importance of subtype-specific use of drugs such as glucocorticoids, and might prompt re-evaluation of previous clinical trials that did not classify people’s tumours by their receptor status.

Moreover, Padrão and colleagues’ insights illuminate a new target that could counteract acquired treatment resistance to tumours that express ERα. The authors provide strong justification for testing hormone molecules known as corticosteroids and for examining modulators of the glucocorticoid receptor, in combination with endocrine therapy, with a view to potentially reshaping clinical standards of care for this form of breast cancer.

Several commercially available, low-cost and well-characterized molecules that activate the glucocorticoid receptor could rapidly be repurposed for studies of whether they improve responses to endocrine therapy, without the need for further drug development. These include molecules such as prednisolone, methylprednisolone and hydrocortisone, which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, these can affect metabolic processes and cause toxicities associated with suppression of the immune system8 and, in some cancer contexts, might lead to other adverse effects. Such issues are therefore likely to limit their widespread use in breast cancer therapy.

Fortunately, a class of molecules that can selectively modulate glucocorticoid-receptor signalling is rapidly emerging. These preserve the beneficial aspects of steroid hormones in modulating signalling pathways but have fewer side effects, particularly in terms of the immunosuppressive effects that are of concern in cancer therapy.

A promising selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator is the molecule vamorolone, which the FDA has approved for clinical use to treat the condition Duchenne muscular dystrophy. This molecule was developed to combat some of the anti-inflammatory effects mediated by glucocorticoid receptors that can adversely affect metabolism and the immune system9. Furthermore, several other such molecules, including the molecule mapracorat, are in clinical development or being examined using animal models.

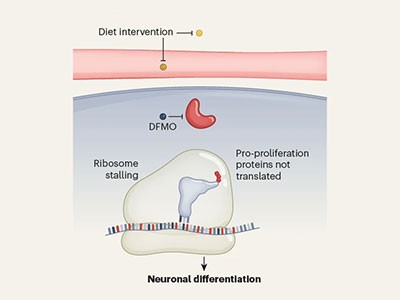

A drug–diet combination could improve childhood cancer treatment

Studies of such molecules demonstrate that they have potent anti-inflammatory activity and low toxicity in preliminary trials10. For example, the molecule AZD9567 has anti-inflammatory effects but, unlike most glucocorticoids, causes minimal bone loss and only small increases in blood glucose (hyperglycemia), and thus should have a lower risk of causing diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the bone condition osteoporosis compared with classical glucocorticoids11.

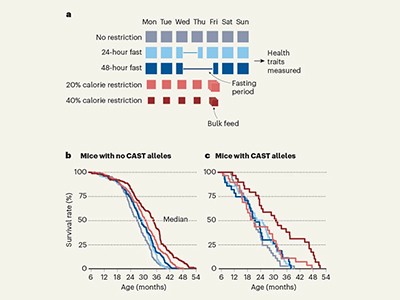

Dietary interventions known to enhance glucocorticoid receptor signalling might be an important addition to endocrine therapy under certain circumstances, either alone or in combination with a glucocorticoid or a selective modulator of glucocorticoid signalling. Such interventions include fasting or fasting-mimicking diets, both of which Padrão and colleagues showed to be highly effective at enhancing the anticancer effects of endocrine therapy. A fasting-mimicking diet involves a five-day-per-week, plant-based diet regimen designed to trigger fasting-like metabolic benefits while providing low-calorie, low-protein food intake.

Other dietary patterns that show some of the same metabolic benefits of fasting include intermittent restriction of calorie intake and what are known as ketogenic diets (low-carbohydrate, high-fat regimens). Each of these diets12,13 reduces bloodstream levels of the metabolic hormones insulin, leptin and IGF1. A dietary intervention might improve the response to endocrine therapy by decreasing the growth-promoting signals that drive ERα-positive breast-cancer resistance.

Padrão and colleagues’ insights are of particular clinical interest, given that reintroducing IGF1, insulin or leptin into fasted mice that were given tamoxifen reduced the antitumour effects of fasting and curtailed fasting-induced increases in the levels of the hormones corticosterone and progesterone. These findings suggest that lowering the levels of one or more of IGF1, insulin and leptin in the bloodstream has a causal role in mediating the anticancer effects of fasting.

The authors showed that treatment with dexamethasone, which reproduced the beneficial effects of fasting on endocrine therapy, also decreased the level of IGF1 in the body. IGF1 is a diet-responsive, pro-survival and proliferative signal in breast cancer that activates a signalling pathway called PI3K–AKT–mTOR. This promotes cell growth, blunts the effects of endocrine therapy and drives treatment resistance14. Thus, IGF1 reduction is a plausible contributor to the antitumour effect that Padrão and colleagues observed arising after a combination of fasting or dexamethasone and tamoxifen treatment.

Dietary restriction can extend lifespan — but genetics matters more

The use of drugs called glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists is rapidly increasing in several countries, including in the United States (see go.nature.com/4tnhjdt). These molecules can drive metabolic reprogramming that mimics fasting and induces anticancer effects, including in ERα-associated breast cancer15. For example, tirzepatide, which is FDA-approved for weight loss and type 2 diabetes, reverses the pro-cancer effects of obesity in mouse models of breast, endometrial and colon cancer15,16.

The effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists also have several mechanistic overlaps with fasting that are implicated in enhancing endocrine therapy, including a reduction in insulin, leptin and IGF1; lower oestrogen levels; and induction of metabolic stress signals known to converge on nutrient-sensing pathways, such as PI3K–AKT–mTOR and AMPK signalling.

This positions these molecules as a possible pharmacological tool to mimic fasting. They might act upstream of glucocorticoid receptors and other metabolism-regulating pathways to influence the response to endocrine therapy. However, information is needed regarding the ability of these molecules to reproduce fasting-like activation of glucocorticoid receptors and to reduce resistance to endocrine therapy. This should be investigated using animal models and clinical trials.

Padrão and colleagues’ insights highlight an emerging opportunity to use metabolic modulation — whether through fasting, other diet regimens, drugs that target glucocorticoid receptors or those that mimic the effects of fasting — to enhance endocrine therapy. Advances in this area might reshape future treatment options for breast cancer.

Source link