That question was posed in the WSJ, and poses three possible answers:

There are three possible answers:

First, it’s too early to tell. Most of the tariffs announced haven’t been in place long. …

Which leads us to the second possibility—the tariffs thus far have just not been big enough to cause the harm economists warned us about from full-on protectionism. The U.S. is a relatively closed economy …

So third, and tantalizingly, perhaps the conventional wisdom is wrong. Or, more precisely, since no one can deny the effect of taxes are real, perhaps, in their rush to emphasize the negatives, economists have overlooked the countervailing forces at work with tariffs: The redistribution of the burden of duties between foreign exporters, U.S. importers and consumers may be reordering the balance of benefit between domestic and foreign businesses and between companies and consumers. Federal tariff revenue up to $300 billion a year will produce gains for Americans.

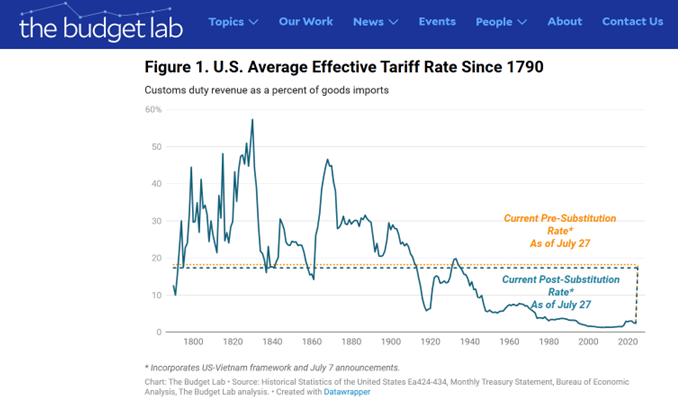

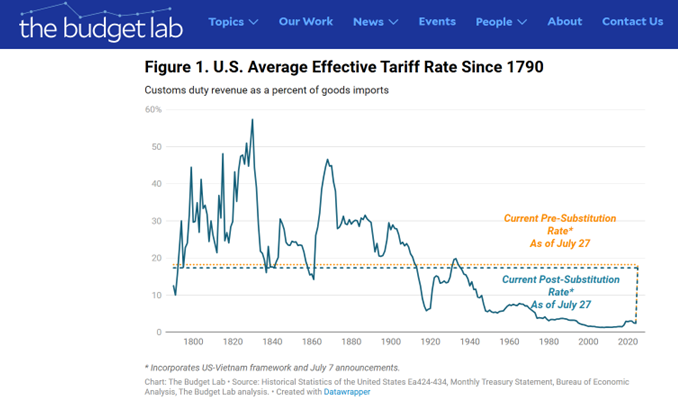

On count 1, I’d remark that most of the tariffs haven’t into play yet. See the effective tariff rate as calculated by the Budget Lab.

Source: Budget Lab, accessed 7/28/2025.

Baker also doesn’t mention the buffering effect of pre-tariff inventory accumulation, which is strange as most of the economics commentary mentions this factor.

On the second point, it’s true the US economy is relatively closed as compared to say UK, or Singapore in an extreme example. But it’s more open than it was just 50 years ago, and more of the trade is of differentiated goods, included in value chains. That magnifies the impact of tariffs. So I think when the tariffs are actually in place, we will see effects (although with USMCA exemptions still in place, we won’t have it as bad as it could be).

The third point is one where Baker is trying to channel the optimal tariff theory. There is a tariff rate that — given the elasticities — maximizes welfare for the country imposing tariffs. But in general such tariff rates are not typically 10-15%, since the US is not a large economy in the context of other countries’ exports. Moreover, empirically, in the 2018 trade war, prices did not behave in a way consistent with this thesis. Most of the burden was borne by US consumers (broadly defined as domestic households, firms, workers). See pp. 133-34 in Chinn and Irwin, International Economics (CUP, 2025).

Source link